“Power to the People”: Gary Williams on Oakland, Berkeley, and the Bay’s Growing Divide

5 min read

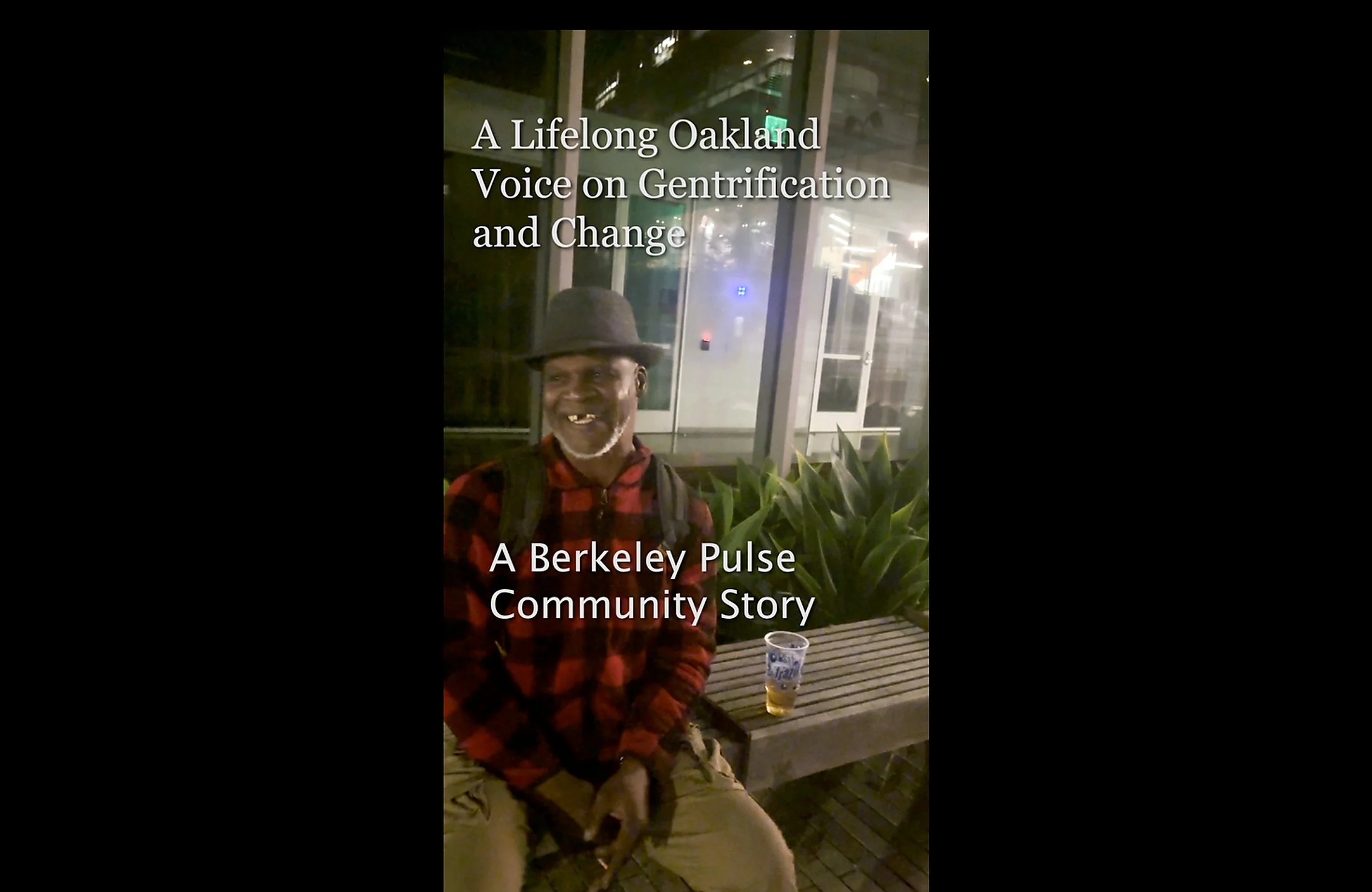

Williams, a lifelong East Oakland resident, reflects on family, displacement, and why Berkeley’s protest tradition feels quieter as wealth reshapes who gets to stay.

I spoke with Gary Williams outside of Hellen Diller Anchor House and learned about his reality living in Oakland and Berkeley since the 1960’s.

Berkeley has always been a place where culture shows itself in public. To Gary Williams, it’s long been “a hippie town” — a city with a reputation for free expression, protest, and a kind of everyday unpredictability you don’t have to search for.

But when Williams talks about what’s changing in the Bay, he doesn’t start with aesthetics. He starts with economics — and with the feeling that more and more places are being redesigned for people who can afford to arrive late.

“It doesn’t matter really where you go today in the United States,” Williams said. “The division between the rich and the poor — the divide is becoming broader and broader.”

Williams is from East Oakland. He grew up on “82nd Avenue between MacArthur and East 14th,” he told me, and he’s spent enough time in and around Berkeley to recognize the region’s contradictions: activism and ambition, community and displacement, pride and loss. In our conversation, he moved between family history and political critique with the same urgency — as if both were proof of what matters.

Where he comes from

Williams described growing up in apartment buildings in East Oakland, raised by parents who worked steady jobs.

“My mom was working at the post office,” he said. “My father was a waiter.”

When he spoke about his father, the tone softened — less analysis, more reverence. Williams said his father worked in Bay Area restaurants in the 1970s and remembered him as someone who broke barriers in spaces where Black workers were often excluded.

“He was the first Black man… the first Black waiter to ever work at Spenger’s,” Williams said, describing his father’s time at the Berkeley restaurant. He said his father later moved to San Francisco and, in his memory, “was the first Black man that ever worked at Alioto’s.”

Williams placed these memories in a timeline anchored by grief. He was born in 1966, he said. His father died in 2012 from lung cancer. When it happened, Williams said, he was incarcerated.

“My brother sent me a letter,” he recalled. “He said, ‘Hey man, pops is gone.’”

He paused, then said what he has carried since: “That dude right there — I never ever, ever felt that he didn’t love me.”

Williams described a father who stayed reachable — “always a phone call away” — and who showed up for him in real ways. “He bailed me out of jail a couple of times,” Williams said. “So one thing I respect about my pops is he always loved me.”

His mother, he added, still lives in the Oakland Hills and is retired from the post office.

Oakland’s map of inequality

When Williams talks about Oakland, he talks like someone reading a city’s power structure off its neighborhoods. Some areas, he said, are insulated. Others absorb the pressure.

“East Oakland, it’s bad news, man,” he said. “It always has been.”

He contrasted that with areas he described as stable and protected. “South Oakland is fine. Lake Merritt, that’s fine,” he said. “All the nice places continue to be nice places.”

Then he described what he sees as a familiar pattern — neglect followed by transformation, but not for the people who lived through the neglect.

“When everybody’s gone, right,” he said, “the white folks is going to move in. They going to jack the prices up… and you ain’t going to be able to move back in there no more because the prices of rent is going to be too high.”

Williams framed gentrification as intentional — a process that pushes people out and then locks them out.

“There’s a reason why they took all that money out of Oakland,” he said. “They want Black people to get up out of there and then when they reinvest, they’re going to jack up everything so high… you ain’t going to be able to live there no more.”

What stays with him isn’t only the policy. It’s the emotional whiplash of returning to places that no longer feel like home.

“When you change buildings,” Williams said, “and… things change from the way they were when you were there… it makes it look very different.”

Berkeley: steadied by the university, reshaped by money

Williams said Berkeley feels different from Oakland in one key way: scale. “Berkeley is a college first of all,” he said. “It’s a very small town.”

And yet, he believes the same pressures are present — just expressed differently. He pointed to the university as a stabilizing force.

“That university — Cal Berkeley — that’s going to keep things rocking,” he said.

In the same breath, he described changes he sees as proof of a shift in power: “People’s Park is closed down,” he said. “The homeless people have lost their fight. Big business has moved in.”

He acknowledged that Berkeley still feels like Berkeley — but to him, it’s also being modernized in a way that sends a message about who the city is built for now.

“You go down the Telegraph,” he said. “There’s a lot of big buildings there.”

For Williams, those buildings aren’t just architecture. They’re evidence of a widening gap he sees across the country.

“They’re making it either you have or you don’t,” he said. “Either you have or you don’t have.”

“Our voices have gotten small.”

When I asked what people can do — how they can respond to this growing divide — Williams answered with a principle before he offered a plan.

“By doing what I’m doing,” he said. “By speaking the truth.”

Then he moved from truth to action. “Go to Congress,” he said. “You have to go to Washington. You have to petition. You have to protest. You have to campaign.”

His argument wasn’t that protest is symbolic. It’s that protest is leverage — and that leverage disappears when people stop believing they have it.

“There was a time… when Berkeley was the protest center of the world,” Williams said, pointing to the 1960s and 70s. He referenced the Black Panthers and the organizing traditions that shaped the city’s identity. “Our voices have gotten small,” he said. “We need to get out in the streets. We need to march. We need to protest.”

Williams also emphasized collective economic action — boycotts — as a way to remind institutions where their power comes from.

“The power is with the people,” he said. “If the people unite and get together… we’re the ones that’s paying all these bills. It’s coming out of our pockets.”

His frustration sharpened when he described what he sees as disunity: people “corrupted by money,” pulled apart by status, distracted by the promise of lifestyle.

“United we stand, divided we fall,” Williams said. “The people are divided right now.”

“Power to the people.”

To close, I asked Williams for three words to sum up what he was feeling.

“Power to the people,” he said.

He repeated it again — not like a catchphrase, but like a warning and a hope at the same time. Without collective action, he believes displacement will continue. With unity, he believes change could come faster than people expect.

“Without us,” he said, “nothing’s going to work.”

Before we finished, Williams spoke about voice as inheritance — something passed down through family. He said he’d been told it came from his grandmother, to his father, to him. Then he began to sing, performing a Spinners song that his father used to sing — a soft ending to a hard conversation, and a reminder that memory lives in sound as much as in politics.